Aug 16, 2025

Story of Your Life

In the last post I described the hypothesis that our everyday, fuzzy concepts have an underlying mathematical structure, and that the meaning of these concepts can be formally expressed in terms of Quality.

To explore this further, let's turn to another story by Ted Chiang: Story of Your Life, the inspiration for the movie Arrival. It follows a team of linguists as they attempt to decode a highly advanced alien language.

The only way to learn an unknown language is by interacting with a native speaker, and by that I mean asking questions, holding a conversation, that sort of thing. Without that, it's simply not possible.

Colonel Weber frowned: "You seem to be implying that no alien could learn human languages by monitoring our broadcasts."

"I doubt it. They'd need instructional material specifically designed to teach human languages to nonhumans. Either that, or interaction with a human. If they had either of those, they could learn a lot from TV, but otherwise, they wouldn't have a starting point."— Story of Your Life, Ted Chiang

This post I'll try to show that there is a starting point: the structure of story itself; that a story is the vehicle for conveying meaning; that stories can be described symbolically in terms of Quality; and that within this structure concepts themselves can be represented precisely, mathematically.

"Story is the smallest unit of meaning"

We'll build on Jordan Peterson's Maps of Meaning framework [^1]. For Peterson "story is the smallest unit of meaning":

"The point of the story is the point—it's directional. I went from here to there—that's the point. That's how I did it. And you're interested, because you may want to do it too."

— Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning lectures

If you've seen Arrival or read the story, you'll remember that aliens and humans learn each other's language by enacting roles and playing out specific stories that embody a concept. For example, they show a fruit and eat it, then display the corresponding words. Or they walk across the room and say "walk".

This works because both sides share a basic assumption: these stories show purposeful movement toward better states (e.g., humans eat to sustain their state of Quality). Without that directional "why," actions and objects cannot be interpreted in a meaningful way.

We can only interpret the meaning of things within the context of a story.

If we can formalize this assumption mathematically, we can begin to represent stories symbolically. The idea is to abstract concepts like walk and eat from their concrete demonstrations and express them directly as mathematical structures. Two beings—human or alien—could then communicate meaning without the need for pantomime.

The frame

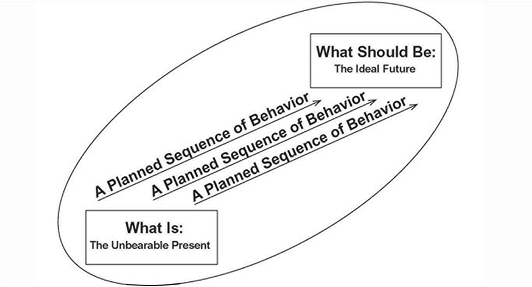

Peterson encapsulates the structure of a story in a cybernetic concept of a frame of reference —

The idea is that we're always operating within some frame, given by where we are (point A) and where we want to be (point B). Where we want to be is somewhere better otherwise why bother going there?

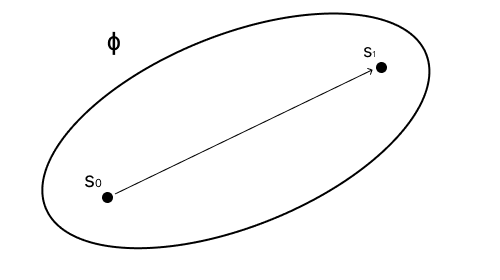

This frame will be our basic template for a story. We'll represent it with and define it by its initial state and the state the agent is aiming at .

While this definition doesn't tell us much of what's going on, it gives us a basic template that must be shared by all life forms: they inhabit some state , and aim toward a state they feel is better, .

"Better" is what Quality is about.

If the states and are in some state of Quality, we can think of the Value of the frame as the difference in Quality between those states:

For example, an animal's hunger puts it in a frame where is hungry and it's looking for food. If is higher in Quality, the Value is positive and the story leads to somewhere better (satiated); if is lower in Quality, the Value is negative and the story leads to somewhere worse (eaten by a predator).

So we have our simplest story structure defined by two states of Quality: .

That's our starting point.

Tools and obstacles

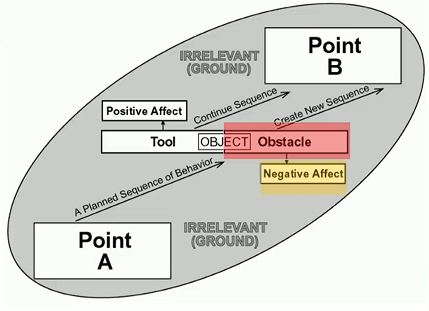

For Peterson, the most basic differentiation of meaning is whether the thing advances the story (tool) or obstructs the story (obstacle) —

In other words, things mean what they do for the direction of the story. The thing either improves the Quality (tool), or decreases the Quality (obstacle), or it has no perceptible influence (irrelevant).

For example, when we want to go out for a walk, we'll perceive shoes as useful within that frame, and we'll put them on.

There's a way of stating this idea that makes it easier to formalize.

When we want to enter the walking frame we can imagine a set of counterfactual frames. For example a frame that includes these shoes, a frame that takes that route, and so on. We tend to select the counterfactual scenario that appeals to us most — one that seems to have most Value. We select it and then we live it out.

If we start with some baseline frame and imagine a counterfactual frame that includes a variable (like shoes), we can compare the Value of those two frames. If the Value of the counterfactual frame is more than the baseline, then the addition of was positive; if not it was negative.

We can define potential [^2] of a variable as the expected marginal Value of , which is the difference in Value between the two frames:

Relative to any given frame, tools are the things with positive potential; obstacles are the things with negative potential.

- — is a tool

- — is an obstacle

The meaning of the entity inheres in its potential relative to the frame. When the frame changes, the potential of the thing changes, and the perceived meaning changes.

For example, in the sitting frame a chair is perceived as a tool with positive potential; in the dancing frame it is perceived as an obstacle with negative potential. The perceived meaning of the object follows its potential, which depends on the frame.

That is the first level of meaning: division of things into useful and not useful, tools and obstacles, good and bad.

Layers of meaning

A thing's meaning unfolds in layers across the stories it participates in.

The tool that enables the sitting story is a "seat". All things that have high potential within the context of this frame will be perceived as seats.

Without knowing the sitting story, the meaning of the "seat" cannot be understood. Carl Sagan's fictional floaters that evolved in the clouds of Jupiter would be oblivious to the sitting story and couldn't conceive of its conjugate concept of a "seat" .

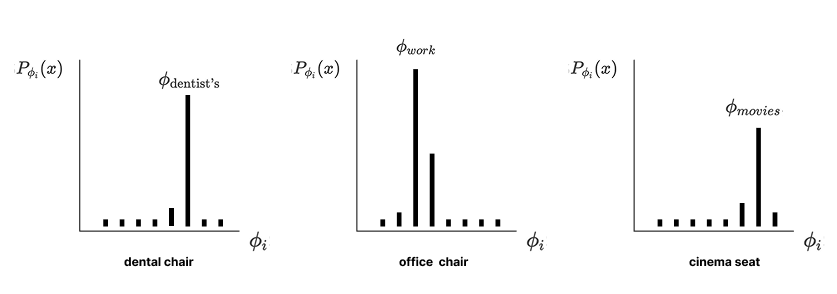

This means that the meaning of a thing unfolds within the stories in which it can be interpreted. If one also knows the dentist story, or the office story or the movies story, one can perceive additional layers of meaning in the seats used in those contexts (dental chair, office chair, cinema seat).

It follows that the more stories the thing can be interpreted in, the richer its meaning and the deeper the understanding.

While a simple story is about bringing an agent into a relationship with a seat, the more complex stories ( , , ) enrich the context by bringing the agent into relationship with tertiary objects (e.g., dentist, office desk, cupholder). If one is familiar with these stories one can interpret different layers of meaning that are impressed into the design of these seats.

The thing in itself

So far we've talked about meaning as a purely relative phenomenon: the thing's meaning is in its potential relative to the frame of reference. But if we want to describe a mathematical essence of the thing — like a chair — there has to be something intrinsic about it that makes it itself, that gives it its identity and that distinguishes it from other things.

A chair and a tree stump can both be perceived as chair-like, because they both afford the sitting function — they both have positive potential relative to .

We can clearly distinguish between tree stumps and chairs, so what makes them different?

The main intuition is that if a thing is designed for some kind of frame, it will tend to have more positive potential within that frame than in other kinds of frames.

A chair tends to be more useful than a tree stump in the sitting frame, because it was designed for it. Its potential relative to that frame is higher. It is meant to be a chair — its purpose is to afford sitting.

We can start to formalize this intuition in the following way:

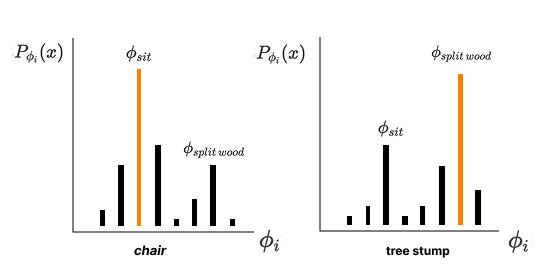

Consider the set of different kinds of stories . If we plot the potential of the thing relative to each frame in the set: , ..., , we'll get some characteristic distribution of potential —

What makes the thing a chair is that its distribution of potential peaks in the sitting story. While it can be marginally useful in many other stories, what gives the chair its identity is that it is most useful as a chair.

A tree stump is a tree stump for a similar reason (although I don't think "splitting wood" is the defining story for the tree stump).

This means that things have both relative (frame-dependent) meaning and inherent (frame-independent) meaning. When using a chair as a weapon, we still recognize it to be a chair. While using tree stump as a seat, we still know it to be a tree stump.

Things have some intrinsic meaning. This means that their essence — their quality — can potentially be captured mathematically.

The quality of things and their Quality

Not all chairs are the same.

An office chair will be more useful in the office work story, a dental chair in the dentist's story, and a cinema seat in the movies story.

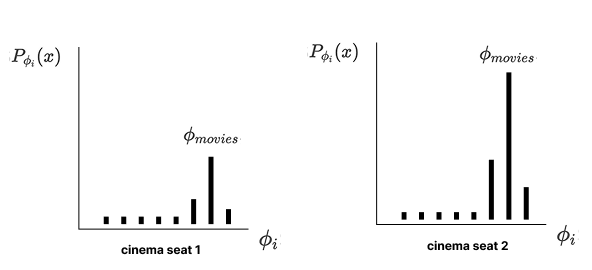

The distribution of potential will be different for these different kinds of chairs. The shape of this distribution corresponds to the "quality" of the thing:

Some chairs are better than others.

A cinema seat that has a greater potential for making progress in the story is a better cinema seat. It might be the right level of comfort, the fact that the shape mostly hides the person in front, that it holds the drinks, or that it satisfies any of the hundreds of relevant subframes. It doesn't matter why it's better; what matters is that it affords greater immersion in the movie.

A philosopher’s stone is a mythical object that’s useful in any story you happen to be in. If you’re hungry, you can eat it; if you need to travel, you can ride it; if you’re hurt, it will heal you. Its potential is positive across a wide range of frames . If you plot those potentials as a histogram you get a broad, high profile. The sum of its potentials across stories — the area of the histogram — is more than a single-purpose tool (say, a corkscrew), which has a narrow spike in one frame and near-zero elsewhere. Philosopher's stone spreads potential widely, so its Quality — and — is high.

A modern near-equivalent to philosopher's stone is a smartphone. It's useful in navigation, communication, payments, entertainment, work, safety, and countless other frames. Because day to day we don’t know which story we’ll enter, an object with broadly positive potentials has the highest expected payoff, and because it fits into our pocket we rarely leave home without it.

This definition of Quality connects back to how we defined Value: . What does a "better" state mean? It essentially means that the agent has greater potential within a single story or across a wider range of stories. A healthier and energized person has more potential to make progress across a wider range of stories than a sick and tired person.

Language of meaning

We understand each other to the extent we share the same stories. The more the cultures differ the less shared stories and interpretative frameworks they share. We can assume that the overlap with aliens would be even less.

We haven't defined the stories like above. We know these stories, but aliens wouldn't necessarily. Even if they share the same story, their morphology could be so different that their chairs wouldn't be recognizable to us — and vice-versa.

These stories would have to be abstracted out of their concrete context. Like Plato's eternal forms, they would have to be free of appearances. Just as the equation is an abstract expression for a circle, this framework's stated assumption is that such abstract expressions exist for more complex concepts like sitting and seats. It is these abstract forms that would be meaningful for cross-culture and cross-species communication. Regardless of our apparent differences, we inhabit the same basic story—Quality—through which contextual differences could be dissolved in this process of abstraction.

Although the current framework isn't expressive enough for representing these kinds of stories, there's a way to think about them that hints at the possibility that they could someday be defined more rigorously:

Consider that sitting is no different from other things with potential. Sitting has some directional purpose within a larger story, some potential, otherwise why sit? Sitting can be thought of as an invariant pattern that brings a gravitationally-bound agent into a specific relationship with an object (a seat) that affords a stable, low energy configuration. The concept of a seat becomes a conjugate expression of the sitting story — it is the object that affords sitting.

This kind of abstract definition doesn't focus on the appearances of sitting and seats. It frames the sitting story in terms of Quality: if you keep asking why—why sit, why rest, why choose this position—the answer always reduces to because it is better. And “better” is precisely what Quality defines.

If we can compress our stories into mathematical expressions that resolve into Quality, we might one day communicate meaning by exchanging a catalog of symbolically-defined stories, much as we transmit information today—through bits and shared encoding schemes.

The fact that we can nowadays represent photorealistic virtual realities and movies like Arrival with a series of 0s and 1s suggests a future where meaning itself can be represented through mathematical structures.

Next...

In this post I wanted to paint a broader vision for this framework. The notation is oversimplified, and the graphs are just meant to illustrate a concept; they're not rigorous or practical in any way—chairs and tree stumps will have to wait. That said, the same ideas can be used for more immediate and practical application. With slight adjustments to the math, it becomes possible to formalize concepts like trust and reputation and use them for designing systems based on trust and reputation.

[1]: For a more approachable introduction to Peterson's framework, I recommend watching his YouTube lectures, in particular: Story and Metastory (Part 1), which is relevant to this post.

[2]: Potential is another concept by Jordan Peterson: Potential: Jordan Peterson at TEDxUofT.